Jet Fighter School II

More Training for Computer Fighter Pilots

by Richard G. Sheffield

Part 1 - Introduction to Aerobatics

Chapter 1

The History of Aerobatics

A common notion is that aerobatics and stunt flying were developed during World War I when planes were first used in combat. This is far from the case. The history of aerobatic flight significantly parallels the history of flight itself.

The Origins of Aerobatic Flight

The Wright brothers themselves performed the first aerobatic maneuver (a 360-degree banked turn) in September of 1904. The key word here is banked because this was prior to the invention of the aileron. The Wright flyer used a wing warping system to flex the entire wing in order to bank the aircraft.

The whole idea of banking the aircraft greatly speeded up the development of flying machines in the United States. The Europeans considered the idea unsafe and unnecessary. They tended to view the airplane as a flying automobile which could be steered around without tilting the wings: an idea that limited their progress for a number of years.

While the Wrights were perfecting their flight control system, even better systems were being developed elsewhere. Dr. William Christmas in Washington, D.C., and a group headed by Glenn Curtiss and Alexander Graham Bell, almost simultaneously developed the aileron.

The Curtiss machine featured an aileron control surface mounted between the biplane wings, close to the tips. Dr. Christmas, however, had a better idea and integrated the aileron as a hinged section in the wing itself--a concept still used today. While Curtiss and the Wrights argued over infringement of the Wright's wing warping patent, Dr. Christmas quietly received a patent for his design. In fact, congress later paid him $100,000 to compensate him for the use of ailerons in all aircraft built during World War I. I mention the aileron because it is the main development that led to more complex aerobatic maneuvers.

By 1909 the Europeans were starting to catch up. In July of that year, a Frenchman, Louis Bleriot, made the first flight across the English Channel. This sparked a widespread interest in flying throughout Europe and America. Flying shows and air meets became wildly popular, and highly profitable for the pilots. Large paying audiences gathered wherever the flyers performed, but they soon tired of simple flying exhibitions and demanded thrills and danger. To keep the crowds coming, the pilots competed vigorously to develop flying tricks and stunts: today's acrobatic maneuvers.

Figure 1-1. A Bleriot Monoplane of the Type Used in the First Flight Across the English Channel

Daredevils

An American, Walter Brookins, captured the attention of audiences with his spiral dives and 90-degree banked turns, still considered wild and dangerous in 1910. Lincoln Beachey countered with his Death Dip, in which he would fly to 5000 feet and dive straight at the ground with the engine off. At the last second he would pull up, often causing quite a stir in the audience as he passed them with both hands off the controls! Beachey loved to scare an audience and would often fly through a stand of trees or under telegraph wires.

As wild as the pilots were during this period, the aircraft often couldn't keep up. Flyers were quickly passing the structural capabilities of the airframe, often with fatal results. In a six-week period in 1910, three of the most famous pilots of the time, Ralph Johnstone, Arch Hoxsey, and John Moisant, were killed when their airframes collapsed while pulling out of diving maneuvers. The press was extremely hard on Beachey and blamed him for many of the deaths because pilots tried to match his skill. They went as far to say that whenever there was a fatal accident, the pilot had pulled a Beachey. Distraught by this and the death of a close friend and team member, Beachey went into temporary retirement in 1912.

Flying at slow speeds resulted in constant danger of a stall and a spin. The result was often fatal because no one had yet discovered how to recover from a spin. Such was the situation presented to Wilfred Parke in August of 1912. He fell into a left-hand spin during a military test. After pulling hard on the stick and pushing the rudder to the left with no result, he eased off the rudder and pushed it to the right, into the spin. The plane immediately righted itself with about 50 feet to spare.

Parke was a detail-oriented test pilot and immediately analyzed and wrote down his experience. Now that someone had entered a spin and lived to tell how to correct it, the mystery of the spin was finally solved. It would take years for the word to spread however, because Parke died shortly thereafter. Eventually the spin would become part of the aerobatic bag of tricks.

Upside Down and Backwards

By 1913, the Europeans were progressing nicely with their French Bleriot and Morane monoplanes and rotary engines. No longer satisfied with normal flight, they began to experiment with unusual flight characteristics. An Englishman, Will Moorhouse, was the first to fly a plane backwards. He pulled up into a steep climb, pulled the nose up as far as it would go, and killed the engine. The Bleriot-type monoplane stopped for a moment and then slid backwards for a short distance before yawing to one side and diving nose-first towards the ground. This later became a standard maneuver know as the stull-turn.

Inverted flight was also being considered. Several pilots had inadvertently found themselves upside down as a result of wind gusts, but no one had yet attempted it intentionally. Adolphe Pegoud decided he would be the one to try.

Pegoud was one of the first true aerobatic pilots. An accomplished test pilot with the Bleriot team, he was also the first flyer to jump from a plane with a parachute. Both Pegoud and the aircraft landed, unharmed. Having decided to try upside-down flying, Pegoud first practiced in a hanger in a plane hung upside down from the ceiling. He correctly assumed the controls would have to be operated in a reverse manner and he wanted to get the feel of it before actually flying.

It must have worked. Shortly thereafter, Pegoud made the first public demonstration of inverted flight in September of 1913. During this flight, he was the first to perform a half roll to an inverted position--another aerobatic maneuver was born. The flight did point out one potential problem: While Pegoud was prepared to fly inverted, the aircraft was not. It proceeded to drench the flyer with fuel!

Until that point the glories of flight had been limited to the Americans and Europeans. In September of 1913 another player entered the picture. A Russian pilot named Petr Nikolaevich Nesterov performed the first complete loop. The first reaction of his superiors was to arrest him for taking undue risks with equipment. Shortly they reconsidered and promoted him.

The name of Petr Nikolaevich Nesterov would surface again in the opening months of World War I. At this time, he was in charge of an air squadron fighting the Germans. When a German plane was spotted over the field, Nesterov ran to his plane and took off unarmed. He approached the German Albatross airplane and tried to destroy it with his landing gear. He misjudged the approach and rammed the German with the front of his monoplane. During the uncontrolled spin to the ground, Nesterov was thrown from the plane. He and the German crew were all killed. Nesterov went down in history as one of the first fighter pilot heroes. He was buried with full military honors.

Suddenly, a looping mania took over. Everyone started doing loops. The loop is even credited with bringing Lincoln Beachey out of retirement. He had Glenn Curtiss design a new plane for him and went on tour performing loops, barrel rolls, spiral dives, and probably many more maneuvers that weren't recorded.

Beachey quickly became the king of the loopers. He was looping all over the country and charging by the loop. He made $500 for the first loop and $200 for each loop thereafter. In 1914 he was earning $4000 to 5000 per week. He frequently flew loops in sequences of ten or fifteen at a time, starting at less than 1000 feet. He was probably also the first person to perform an outside (inverted) loop.

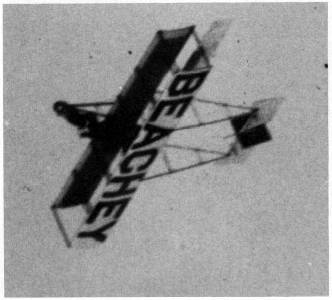

Figure 1-2. Lincoln Beachey, the King of the Loopers, Upside Down

Beachey also worked in aircraft design, developing a sleek monoplane. On March 15, 1915 he unveiled his new design at an exhibition in San Francisco, his home town.

After performing a series of loops, he pulled into an S-dive over the bay. Having flown biplanes for a number of years, he apparently was taken by surprise by how fast the new monoplane dived. He quickly found himself running out of altitude and pulled back hard on the stick. The plane was never designed to perform this maneuver at such high speeds. The crowd stood dumbstruck as both wings snapped off and Beachey plunged to his death into the bay. Orville Wright referred to him as "the greatest aviator of them all."

World War I

By 1914, the word aerobatics was a part of the language both in the U.S. and abroad. Air shows and flying exhibitions were frequent and heavily attended. The sport was healthy and growing prior to the first shot of World War I.

The Great War had enormous influence on aerobatics, as aerobatic tricks and stunts quickly became lifesaving maneuvers in battle.

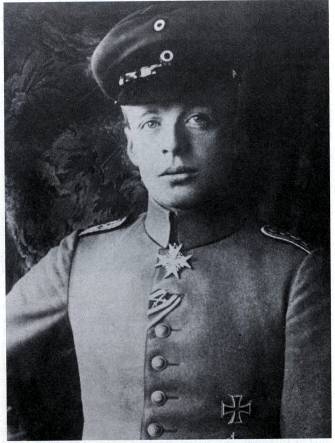

Two innovative Germans, Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann, made their mark in the sport during this period. Boelcke was the master tactician and leader; he developed many of the tactics used so successfully by the German aviators and has been called the "father of air combat." Though the Germans were flying the somewhat inferior Fokker Eindecker monoplane, their superior tactics gave them an early advantage over the battlefield.

Figure 1-3. Oswald Boelcke, Father of Air Combat

Max Immelmann was known for his successful hit-and-run attacks. He was a master of the surprise attack, often coming out of the sun or from underneath his opponent and then using aerobatic maneuvers to get away. His name lives on in modern aerobatics in the form of the Immelmann Turn, an ascending half loop with a half roll. There is a controversy, though, as to whether this maneuver could have been flown in the wing-warping Fokker monoplane. Immelmann is still given credit for using this maneuver to attack from beneath an opponent on the way up, then reverse course and get away. It is more probable that the maneuver used was similar to the modern wing-over or chandelle.

Figure 1-4. Max Immelmann

The war also took its toll on a number of great flyers. The great Adolphe Pegoud was shot down and killed in August of 1915, only two years after he pioneered inverted flight. Oswald Boelcke died in a midair collision in 1916. By the end of the war, a number of new tricks had been added to the aerobatic inventory. Half loops, barrel rolls, and the split-S all became commonplace due in part to the development of the powerful German Fokker Albatross and the English Sopwith. The war also gave aerobatics a valid reason for existence; those pilots who lived long enough to develop their aerobatic skills over the battlefield were the most successful. Despite the obvious importance of this type of flying, formal training courses for the military were not set up until 1917.

Figure 1-5. The Feared German Fokker Albatross

After the Armistice

With the war over, hundreds of flyers had nowhere to fly. The reappearance of the air show was soon to follow. As before the war, a competitive spirit set in among the performers, each trying to outperform the rest. Some of the shows featured the famous barnstormer acts while others pursued the more traditional aerobatic displays. Jimmy Doolittle, who later bombed Tokyo, pioneered inverted flight and revived interest in the outside, or negative G loop. The intense rivalry among the flyers continued to produce new maneuvers. Vertical rolls, flat spins, and vertical figure eights were added to the list as well as the roll on the top of a loop, or avalanche.

This period also featured the first aerobatic competitions. The world's first large scale international aerobatics competition was held in Zurich in August of 1927.

A young German pilot named Gerhard Fieseler had developed such a reputation that he was invited to the Zurich meet. Fieseler wanted to do well and was in search of new maneuvers when the idea of inverted flight became popular again. Several months of intense work produced the first aircraft fuel system capable of sustained inverted flight. Fieseler quickly mastered a series of inverted flight figures which could be flown in any weather.

From the start of the competition it was a three-way race between Fieseler and two French pilots. After a series of compulsory figures and short freestyle programs, Fieseler was still in the hunt. He progressed to the finals where he executed his unique and flawless routine. Fieseler was awarded only second place, however, perhaps for political reasons. Whatever the reason, inverted flight had arrived and would become a permanent part of aerobatics.

Competition aerobatics became a mature sport complete with rules and regulations. International meets became quite common. In the mid 1930s a new force in world competition would emerge from Czechoslovakia. The Czechs had been developing their flying skills since the days of Pegoud and were now ready to show them to the world. They won two of the top three spots in the 1936 Olympic competition and almost all of the titles in Zurich the next year. They were undeniably on a roll. But that roll was stopped cold by World War II.

World War II and Beyond

World War II saw a dramatic increase in the power and speed of fighter aircraft. Due to these high speeds, many of the aerobatic maneuvers of the World War I became obsolete and dangerous. Few aerobatic maneuvers came out of the conflict but a number of important aircraft modifications did result. Seats were modified to help the pilot withstand higher G forces. Straps were placed on the pedals to help keep the pilot's feet from sliding off during maneuvering. The German Stuka dive bomber canopy included marks to identify the plane's dive angle and a window was placed in the floor of the cockpit. All of these changes made their way into postwar aerobatic aircraft.

In the 1950s, just when everyone thought that all possible aerobatic maneuvers had been discovered, the Czechs re-established their leadership in the sport by introducing the lomcovak. This maneuver must be seen to be understood.

Even then it's difficult to comprehend, as many of the first observers found when they tried to repeat what they had witnessed. The maneuver is best described as a series of gyroscopic twists and somersaults during which the plane rotates about all three axes.

Aircraft design improvements continued through the following decades, allowing a few more innovations (mainly in the area of vertical maneuvers) as increased power and lighter aircraft made vertical acceleration possible. The recent emphasis, however, is on the accurate performance of the maneuvers; loops in perfect circles and accurate figure eights have taken the place of dangerous thrill-seeking maneuvers, much to the benefit of the sport and the pilots involved.

As you can see, the history of aerobatic flight is as old and honored as the history of flight itself. Through the years it has been the realm of a few high-spirited and courageous individuals and out of the reach of most people. Now anyone with a computer can share in the experience of a well performed maneuver and in a small way identify with those daring men who pioneered the sport in aircraft made of little more than cloth, wood, and wire.

Table of Contents | Previous Section | Next Section