40 More Great Flight Simulator Adventures

by Charles Gulick

The High

and

Mighty

Mighty

| North Position: 15150 | Rudder: 32767 |

| East Position: 5746 | Ailerons: 32767 |

| Altitude: 1601 | Flaps: 0 |

| Pitch: 0 | Elevators: 32767 |

| Bank: 0 | Time: 6:30 |

| Heading: 247 | Season: 2-Spring |

| Airspeed: 0 | Wind: 6 Kts, 220 |

| Throttle: 0 |

For the past five or six days I've been watching a very young budgerigar (or budgie, or parakeet) make his first attempts to fly. I knew nothing about these birds when I bought one about a week ago. In fact, I knew little or nothing about birds in general. But this little parrot has taught me a few things.

Budgerigar is the native Australian name, derived from the Australian budgeri 'good' and gar 'cockatoo' (though it isn't a cockatoo). Budgie, the Good Cockatoo.

I told the dealer I wanted the bird to be free to fly around my apartment, but it was suggested I have his wings clipped anyway for his own protection. (They'd grow back.) So they were clipped, but on my stipulation that he have wingspread enough to at least glide. This showed great insight on my part, since the idea of gliding has never, from day one, entered Bobbie's mind. When he tries to go anywhere without visible means of support, he flaps his tiny wings madly, from start to finish. Gliding is a luxury reserved for gulls or pelicans or eagles.

Bobbie escaped from the little box I brought him home in as I was trying to slip him into his-not cage-but sleeping and eating quarters. He sort of fell, with a flurry of wings, onto the kitchen floor, then took up a huddled position in front of the dishwasher. After about an hour of coaxing, comforting, and one-sided conversation, during which he seemed sometimes to listen, he waddled to a wicker room divider I had leaning against the kitchen wall and climbed to the top of it via claws and beak. And there, about seven feet above the floor, he perched all night.

I timed Bobbie's arrival to match a week's vacation, so I could "protect" him through his early experiences in my apartment. And so we could get acquainted.

And I've become acquainted with what I regard as a sheer miracle.

I've had the privilege of watching a half-dozen first flight attempts, but, more importantly, the preparation for each of these flights. The initial flight lasted only about two seconds, and wasn't so much a flight as it was a flurry in the direction of the linoleum. He fell from the high perch to the floor in a straight line, with his wings flapping furiously all the way. Then with great dignity he stood up, walked back to the wicker room divider, and clawed and beaked his way back up to his perch.

I applauded and praised him greatly for about two minutes. I do that now every time I see him fly. Because he deserves it. I assure you, if he's any criterion, birds are not born knowing how to fly. They learn it. The hard way. What they do know is that they should fly. From there on out they just work at it.

Bobbie spends about ten minutes doing a preflight number on himself, physically and mentally. Between flights he spends hours, I'm convinced, planning his next.

The physical preflight is just incredible. He works with electric speed over his entire body, preening and pruning himself. The most amazing thing is that he pulls on his wings with his beak to, I believe, widen their span, literally stretch them. He also uses his claws to separate and lean out the tail feathers, and his beak to comb and fine-tune the scapulars, or shoulder feathers, and the fine coverts that overlie the main wings. He nips fluffs of surplus blue down from his breast and white down from way in under his wings. He bites and claws and scratches himself, and twists around so that his head is facing opposite his body. Then he turns on his perch and looks at the wall and shakes all the work down, cocking his head from side to side. He faces forward and goes through the whole process again, biting, arranging, and rearranging each feather as if he knew exactly what its perfect orientation was, tugging again and always on his wings and stretching them as far out from his body as he can. And scratching and shaking. When he's about ready, he chirps shrilly a couple of times (otherwise, he's silent all day). He rehearses his flight again, the one he's been studying for hours, with quick but intent looks toward the top of the refrigerator, the clear sections of the countertop, the floor, and me (wherever I happen to be watching).

Sometimes, after he does all this, he doesn't fly. He's just not psyched up enough. All the fervor seems to leave him, and he slowly and quietly slumps down and gets somnolent.

But when he flies, and each time he flies better, it's a brief moment of rarest charm. The first few times he just flapped to the floor. But back on his perch, he studied the refrigerator top with an intensity that could almost burn a hole. Not for minutes, but for up to an hour. The top of the refrigerator, on the other side of the kitchen from the room divider, is his present target. He hasn't made it yet. In his attempts, he's hit the refrigerator door a couple of times, then flapped on down to the floor. Another day, realizing the refrigerator was beyond his immediate capability, he decided what he needed was directional control. However, he flew to the left instead of the right to avoid smacking into the door and fell right on down into the bottom of an empty wastebasket.

But he climbed up on his perch again and studied. He thought about what he'd been doing wrong. And this morning he's begun to learn about direction. After a long preflight, he leaned far forward on his perch-his eyes bright and his whole body seeming to thin out and streamlinelaunched himself, and flew toward the kitchen counter next to the refrigerator. Aware when only two-thirds of the way there that he couldn't get or hold the necessary altitude, he turned right in a beautiful arc, flew a semicircle downward, and made a superb landing on the floor. This time, too, for the first time, he chirped as he walked to the divider. He was delighted with his achievement. He knew, exactly now, how to turn right to get out of trouble.

And I'm convinced a left turn will be the next study. Meanwhile, he's getting closer and closer to making it to the refrigerator top, which is about the same altitude as the wicker perch. He'll force those wings to spread. He'll just pull them out to where he wants them, spreading them by sheer determination. He'll lean himself out and work himself over fiercely until he has his body down where he wants it. He's going to be swift, sharp, sure. And I'm going to be a witness of it all.

I don't care if Bobbie ever talks, and says hello or pretty bird or I love you. Or if he learns to climb on my finger. That he flies is what matters. That's why I've given him the biggest cage I can-my entire apartment.

When the great American contralto, Marian Anderson, visited the mighty Finnish composer, Jean Sibelius, he greeted her with these murmured words: "I am only sorry that the roof of my house is not high enough for you."

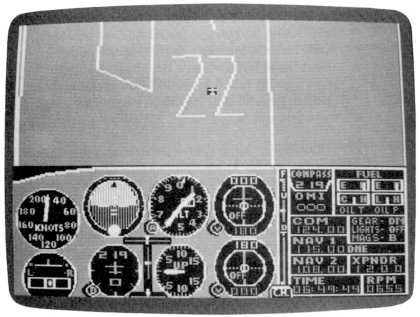

The airport with the highest elevation in the simulator world is on Santa Catalina Island, off the coast of California. This mode gives you a convenient tie-down there, just off the taxiway at the business end of runway 22. It's yours. Permanently. Out there surrounded by ocean. Up there surrounded by sky.

Fly.

Table of Contents | Previous Section | Next Section